Defining, Determining, and (humbly) Demanding a Farm Profit

By Katelyn Walley-Stoll, Farm Business Management Specialist and Team Leader with Cornell Cooperative Extension’s Southwest New York Dairy, Livestock, and Field Crops Program

Profit. It seems that the term “profit” stirs different types of emotion into farmers’ hearts whenever I try to casually bring it up in kitchen table conversations. For some, profit has always been a goal – will always be a goal – and is tracked from year-to-year, or even month-to-month. For others, profit is a lofty idea that, in theory, the farm strives for – as long as they don’t have to pay in any income taxes at the end of the year. Yet, for some, profit is a “bad word” and definitely not the right reason to be in the business of farming.

Wherever your thoughts and gut reactions lie on the profit spectrum, if the farm is being operated as a business, profit will come into play at some point. Understanding what profit is, and the role it plays in farming, is important to reach your overall agribusiness goals.

Defining a Profit

Most of the time, the profit equation is presented as:

Income – Expenses = Profit. Income minus expenses equals profit. Also known as Value of Production less the Cost of Production equals Profit or Loss. So, you start farming and sell what you’ve farmed for income. Then, you subtract out all of your expenses to create that income. And (hopefully) you have a profit at the end of the year and can keep chugging along.

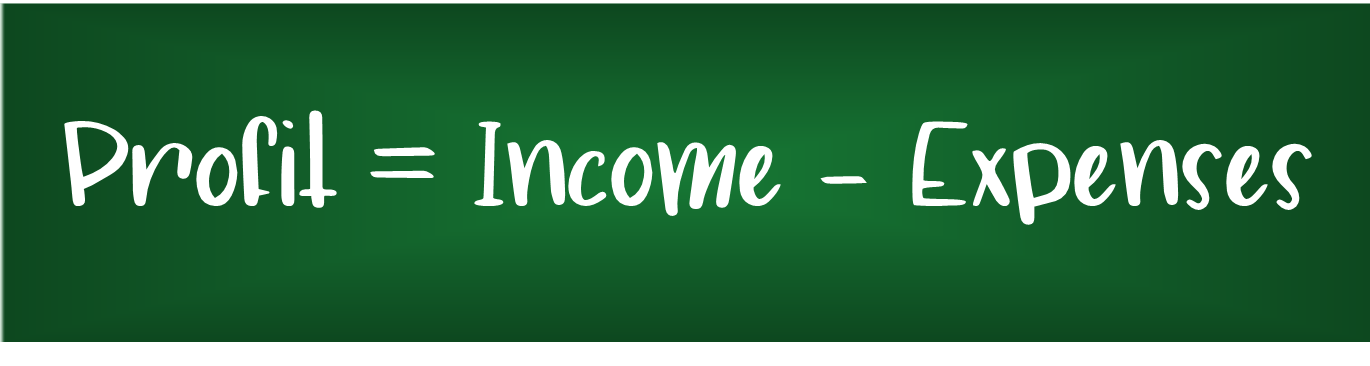

BUT what if we started thinking of the profit equation as:

Profit = Income – Expenses. Now, this is a bit of a thought exercise because both equations will get you to the same point at the end. What would happen if you started farming with profit in mind from the very beginning? It’s so easy to get caught up in the incomes (yay) and expenses (another bill) that you can quickly lose track of your overall financial and business goals. What if you knew what your profit goals were and then planned for incomes and expenses accordingly – instead of just farming how you hope will meet your goals and dealing with whatever profit or loss came at the end?

There are a million different ways to farm, and all of them are right! However, if you’re not monitoring profit and redefining it as a priority, you could be doing everything “right” and never “get ahead”.

*An important note: This idea of switching around the commonly delivered profit equation isn’t mine! I recently spoke with a wonderful person, Goli Ziolek, at the National Extension Risk Management Education Conference. Along with Kate Larson and Ritchie Wai, their team runs “Stateline Farm Beginnings”, based in Caledonia, IL. Learn more about their amazing program here: https://www.learngrowconnect.org/sfb.html.

Determining a Profit

How do you know if your farm is making a profit? It’s so much more than watching your checkbook balance go up and down throughout the year, or guesstimating your assets to liabilities balance. Profit is measured by using your farm’s Income Statement.

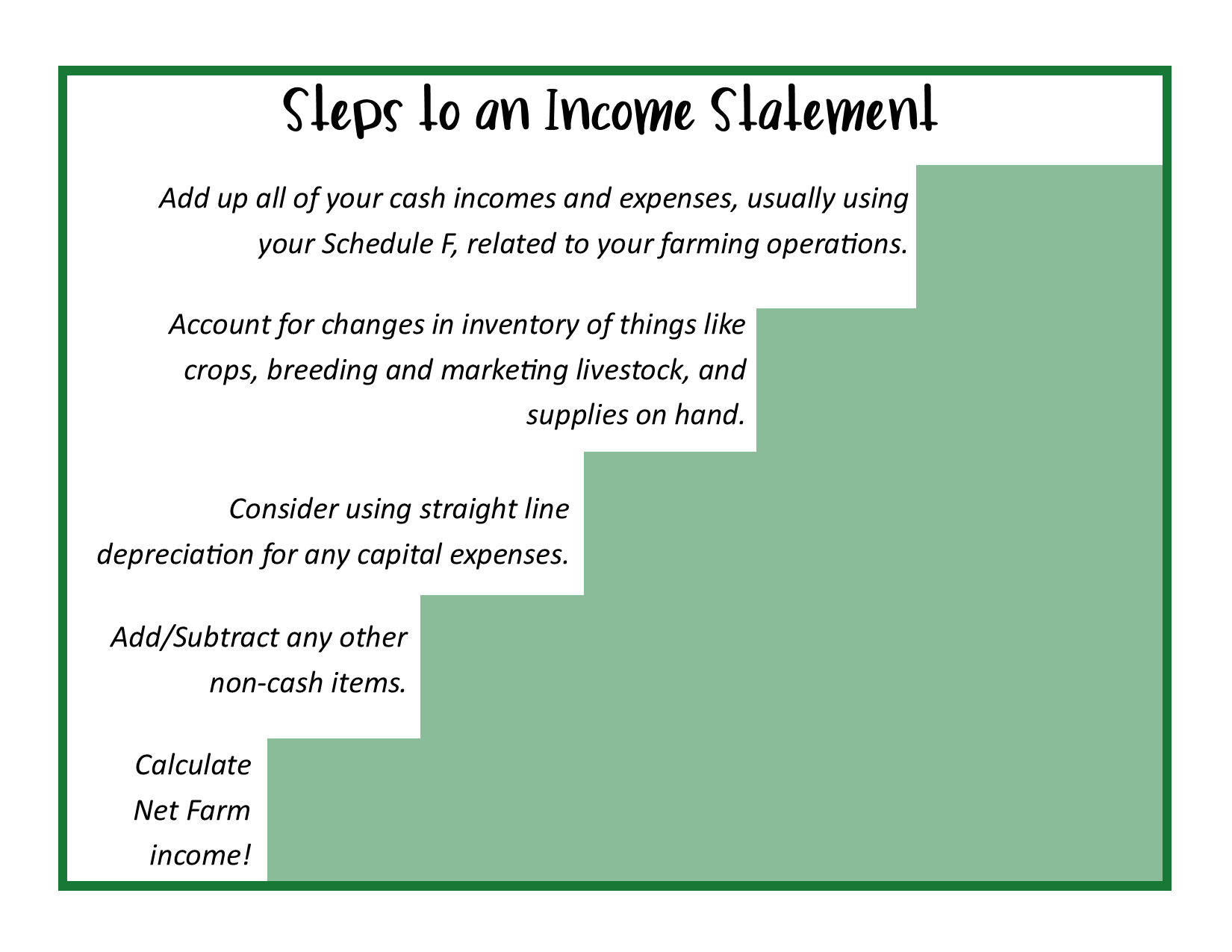

An Income Statement shows your farm’s overall productivity, categorized expenses, and return on investment. This is also called a Profit and Loss Statement. Compiling an income statement isn’t an overly taxing process (pun intended) because many of the numbers you’ll need come right from your end-of-year tax documents.

However, most farms do their taxes on a cash basis, meaning incomes and expenses are recorded as cash leaves or enters the check book. While this is a perfectly acceptable and manageable method for cash-based, farm-business reporting for income tax purposes, adjusting your cash-basis accounting to accrual accounting is one way to accurately measure your farm’s profitability.

Accrual accounting takes into account changes in inventory, accounts payable/receivable, interest, depreciation, and values unpaid labor and management. These are things that have value but might not have a direct line item on a Schedule F or checkbook ledger.

Income Statements have two main parts: Incomes and Expenses. After calculating the incomes and expenses, you’ll make the “accrual” or non-cash adjustments to each to better reflect your farm profitability.

Incomes include cash sales of livestock and their products, crops, government payments and insurance proceeds, and other income streams related to the farm. Do not include any sources of income that are not from the farm (off-farm jobs, annuity or similar payments, etc.) – more on this later.

Non-cash adjustments to income will account for things that provide value to your farm, but don’t show up in the checkbook ledger. You’ll note changes in inventory of feed and grain, breeding and marketing livestock, supplies on hand, etc. This helps make sure the value of a farm product is counted in the year that it’s produced, instead of when it’s sold. An example – you had a really good crop year and put up a lot of extra baleage. Your plan is to store that baleage and sell it in the following year, once winter really hits. But – you’ve already paid to produce that baleage. Without making non-cash adjustments by recording inventory changes, your checkbook balance will see all of the associated expenses (wrap, fuel, twine) but none of the associated incomes (baleage sales). You’ll also note accounts receivable which includes income that you’ve earned but haven’t received. Usually things like the last month’s milk check, an upcoming grape contract payment, or a livestock auction check that hasn’t made it to the bank yet.

Then, you’ll add up the cash expenses of your farm. These, again, would all come from the Schedule F. However, any large capital expenses (land, equipment, big repairs) will not be included here – instead, you’ll use deprecation to account for those expenses. Depreciation is a non-cash adjustment used to show the decline in value of a capital asset over time. You can use the depreciation values on your income tax return, but you might find something like straight line depreciation more valuable and realistic. One other non-cash expense is something called “Value of Owner Labor and Management” which we’ll talk about next.

Summarize the Income Statement by subtracting your total farm expenses from the total farm revenue to get your net farm income.

(Humbly) Demanding a Profit

Now, to the part that will probably make some of you squirm a bit. You should DEMAND a profit from your farm. You’ll see that I graciously added *(humbly)* in the title of this section so you don’t think I’m a completely heartless monster. But – demanding a profit from your farm business is in the best interest of you, your family, your customers/market, and your long-term business sustainability. And here’s why.

As a farm owner, raise your hand if you regularly write yourself a steady, prevailing-wage, paycheck out of your farm business account that fairly compensates you for all of your time, labor, management, and investment…

While I can’t see you as you’re reading this, I’m guessing that your hand isn’t raised. As farm owners, most of the time you’re not receiving a regular draw from the business. And sometimes, you might be using off-farm sources of income to cash flow the farm during lean times. In this situation, a farm profit is – essentially – your paycheck. When you’re only looking at the checkbook balance and cash inflows/outflows, without a profit there’s no paycheck for you, the farm owner.

Calculating your “Value of Owner Labor and Management” can be a scary and humbling adventure, but is important to consider in your farm profitability analysis. This figure can be used as a placeholder for your “paycheck” and represents that time and effort you put into the physical and mental management work on the farm. Consider this – if you weren’t farming, could you earn a paycheck someplace else? How much would that paycheck be? If you’re working as unpaid owner labor on the farm, are you currently earning a profit that’s high enough to value your labor? What’s the value that you’re providing to the farm business if you had to hire someone else for the role?

If you’re still not sold on demanding a profit, your argument is likely something to do with valuing the farm lifestyle, or choosing to raise your family on a farm, or wanting to raise healthy food for your family….And, if you’re absolutely committed to making a profit, you’re probably ALSO farming for any and all of the reasons above. Most farmers don’t farm because they really enjoy paperwork and crunching the numbers. In agriculture, making a profit every single year isn’t a guarantee – but it should always be a goal. While it’s absolutely, positively okay to farm for reasons other than profit, you should at least make sure you’re operating the farm in a financially sustainable way.

When farms aren’t profitable, the farm “loss” has to be made up someplace else. I usually see this coming from sales of capital assets which are things that you’ve purchased and have built equity with over time, or the use of reserves that might have been built in better years. Neither of these are good options for the long-term. There’s also the use of off-farm income to essentially subsidize the farming operation. This shows up in the form of off-farm jobs, utilizing annuity or similar payments, cashing in on retirement accounts, and taking out personal loans/credit cards to make ends meet. While these options diversify farm income to varying degrees, they all carry certain levels of risk that can make it difficult to maintain personally.

How can you “demand” a profit from your farm? Manage it as a business.

- Consider how you’re going to make a profit before incurring incomes and expenses instead of accepting the profit/loss that happens after-the-fact.

- Maintain accurate records that you compile and analyze on a regular basis (including the preparation of an income statement).

- Evaluate decisions not only from a best management practice standpoint but also for their effects on your cost of production and adjust accordingly. Being the best farmer you can be doesn’t guarantee a profit.

- Set profitability goals that will prevent you from using your labor/management and any off-farm income from subsidizing the farm business.

This material is based upon work supported by USDA/NIFA under Award Number 2021‐70027‐34693.